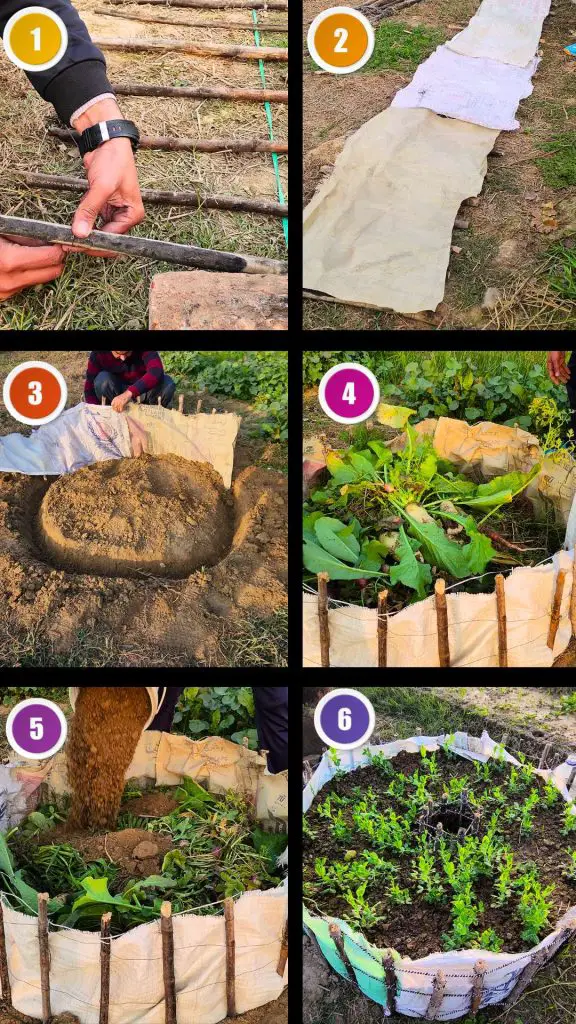

Every garden accumulates materials over time. Bamboo from old projects, wire that has already served its purpose, piles of leaves, grass clippings, and vegetable scraps often end up treated as waste. In reality, these materials still carry value. Bamboo in particular is light, strong, and surprisingly durable when used correctly. Instead of discarding it, cutting it into manageable, equal lengths gives it a second life as a structural element in the garden.

By trimming old bamboo sticks to about one and a half feet, uniformity is created. This consistency is important because it allows the pieces to work together as a single unit rather than as individual poles. When tied side by side, bamboo forms a flexible but sturdy wall that can hold soil without collapsing. Using iron wire instead of rope adds long-term strength, especially in outdoor conditions where moisture, heat, and soil contact weaken natural fibers quickly.

This approach does not rely on perfection. Slight bends or surface cracks in old bamboo do not reduce its usefulness. What matters is how the pieces are joined and supported. Once tied tightly, bamboo behaves more like a woven fence than a collection of sticks, distributing pressure evenly across the structure.

Creating a Soil-Holding Wall With Simple Covering Materials

Bamboo alone leaves gaps, and those gaps must be managed to prevent soil from spilling out. Covering one side of the bamboo wall solves this problem. Cardboard, old sheets, or landscape fabric all work well because they are flexible, easy to secure, and allow slow water movement. The purpose of this layer is not to create a sealed container but to act as a barrier that holds soil while still letting the bed breathe.

Tying the covering material directly to the bamboo ensures it stays in place even after the bed is filled. This layer also plays another role over time. Cardboard and natural fibers gradually break down, adding organic matter to the soil. Instead of becoming trash, the covering becomes part of the growing system.

This combination of bamboo and soft barriers creates a balance between strength and adaptability. The wall is firm enough to hold shape but forgiving enough to shift slightly as soil settles and organic matter decomposes.

Why Circular Beds Offer Better Stability

Shaping the bamboo wall into a circle is not just an aesthetic choice. Circular structures naturally resist outward pressure better than straight lines. When soil pushes outward, the force is distributed around the entire ring rather than concentrated at weak points. This makes the bed more stable even when filled deeply.

The circular form also simplifies placement. Once the ends are secured, the structure supports itself. There are no corners to reinforce and no long sides that bow outward. This shape works especially well for materials like bamboo that are strong lengthwise but flexible across joints.

Beyond strength, circular beds create efficient growing spaces. They reduce wasted corners and make planting, watering, and harvesting easier from all sides.

Anchoring the Structure Into the Ground

A structure is only as strong as its connection to the ground. Digging a shallow ridge or trench, about three to four inches deep, provides that connection. Placing the bamboo circle into this trench lowers its center of gravity and locks it into the surrounding soil.

When soil is packed firmly around the outside of the structure, it acts as a brace. The ground itself becomes part of the support system. This step prevents shifting caused by watering, heavy rain, or uneven filling. Even lightweight bamboo becomes stable once it is partially buried and surrounded by compacted earth.

This grounding method avoids the need for stakes, concrete, or permanent fixtures. The bed remains movable if necessary, yet strong enough to last multiple growing seasons.

Building Fertility From the Bottom Up

The inside of the bed is where the system truly begins to work. Instead of filling it entirely with soil, layering organic materials at the bottom creates a living foundation. Vegetable leaves, kitchen scraps that cannot be eaten, old plant stems, and grass clippings form the first layer. These materials are often abundant and frequently discarded, yet they are rich in nutrients.

Placing coarser materials at the bottom creates air pockets. These pockets improve drainage while also holding moisture during dry periods. As microorganisms break down the organic matter, heat and nutrients are released slowly. This process feeds plants from below rather than relying on constant surface fertilization.

This layered approach mimics natural soil formation, where organic debris accumulates, decomposes, and enriches the ground over time.

Adding Soil Without Losing Air and Structure

Once the organic layer is in place, soil is added on top. This soil fills gaps and adds weight, helping the bed settle and stabilize. It is important not to compact the soil too tightly. Gentle settling is enough. Over-compaction removes air spaces, which are essential for root health and microbial activity.

The soil layer acts as a buffer between decomposing material and plant roots. It allows nutrients to move upward gradually rather than overwhelming young plants. As the organic layer below breaks down, the soil above becomes richer, darker, and more structured.

Over time, this soil improves on its own. Earthworms and microbes move freely between layers, blending organic matter into the growing zone.

The Role of Compost at the Surface

The final layer is compost. This top layer is where seeds germinate and roots begin their journey. Compost provides readily available nutrients and a loose texture that encourages root expansion. It also protects the soil beneath from drying out and reduces erosion during watering.

Compost acts as a bridge between active decomposition below and plant growth above. It keeps the surface biologically active while preventing nutrient loss. With each watering, nutrients move downward, feeding deeper layers of soil.

Using compost as a top layer reduces the need for additional fertilizers. Plants draw what they need as they grow, supported by the steady breakdown of organic material beneath them.

Long-Term Benefits for Soil Health

Beds built this way improve over time instead of wearing out. As organic matter decomposes, it increases soil carbon, improves structure, and enhances moisture retention. Each season adds another layer of roots, residues, and microbial life.

The bamboo structure holds everything in place during this transformation. Even as internal materials settle and shrink, the bed remains intact. The soil becomes lighter, more fertile, and easier to work with each year.

This method reduces the need for constant soil replacement. Instead of removing old soil and bringing in new material, the bed renews itself naturally.